bradipao.net

coding for fun whatever can be coded

Project maintained by bradipao Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

Verona Arena

1 - Planning the plan of the model

In order to use openSCAD to create the Verona Arena model, we cannot start drawing one shape after the other measuring size and position. It would be a huge effort for a modest final result. We need to exploit symmetry and modularity of the structure, but first we have to find some drawings, as much detailed as possible.

Searching on Google for a plan of the amphitheatre returns a couple of excellent results, which are basically a radial structure obtained from concentric ellipses. In theory it should be ideal to procedurally generate the geometry.

Once printed on paper, just with a simple ruler you can find that ellipses have different eccentricity and radial septa (dividing walls) do not converge to the centre, but at least in four different places. Further checks on details of geometry show other asymmetries, that make unlikely to proceed on this path for the automatic generation of the model.

After further searching I found the astonishing work of prof. Camillo Trevisan, a study on the building schemes of the main roman amphitheaters (link). Let’s make it short: even if the actual perimeter of Arena is almost a perfect ellipse, from a building point of view it has been realized with the four centers method for construction of oval shape. It is a geometric construction executed with ruler and compass, that allows to draw an oval almost indistinguishable from an ellipse, using just four arcs of circle.

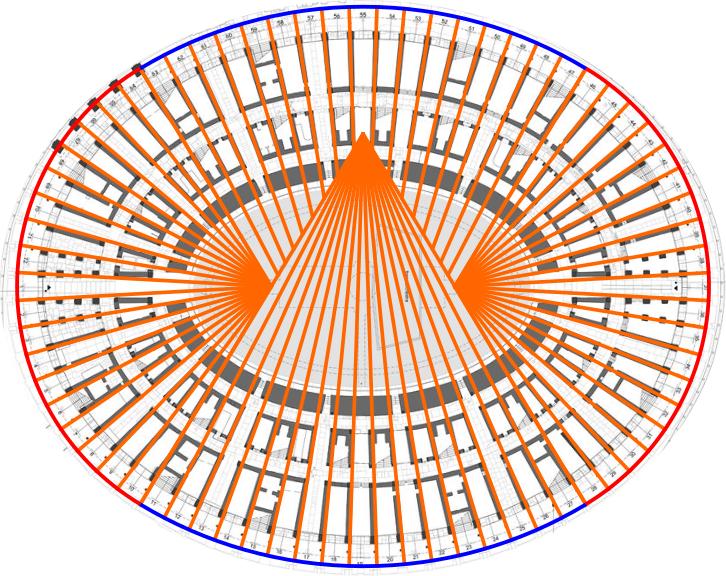

If you recall, I said that radial septa converge in four places. Those places are actually the centers of the four arcs of circles which build the oval. Obviously the arcs need to have different radius in order to have smooth transition between each other at joining points. Then we divide each arc in the exact number of arches on the perimeter of the Arena and overlapping our drawing with a real world plan of the building we find an almost perfect match. Moreover there is a detail I noticed during my visit in the Arena: among the 72 arches on the perimeter, four of them are slightly taller. And those arches, once located on the plan, are exactly at the joining points of the four arcs of circle. All these matches make almost certain that roman architects used this method to place poles connected by ropes on ground, and replicate the above geometrical construction and determine where to place columns and walls.

The simplicity of tools used by builders to draw the geometry of amphitheatre makes it also the best method to procedurally build our model, without sizing and placing each basic block. So, in summary, our procedural method will consist in placing columns, arches and walls at regular distances along the four arcs of circles centered in four specific points, obtaining a shape almost indistinguishable from an ellipse as the actual Arena.

Ok, we have the geometric construction, now we need to know where are the four centers. The easy way would be to prolong the septa until they converge in the four centers and measure their position on the plan. However the approximation would be quite rough and it would likely result in graphical artifacts due to bad positioning and sizing of walls and arches. We need something more precise.

It is better to derive the parameters of the four-centers-oval imposing constraints derived from geometry to mathematical equations.

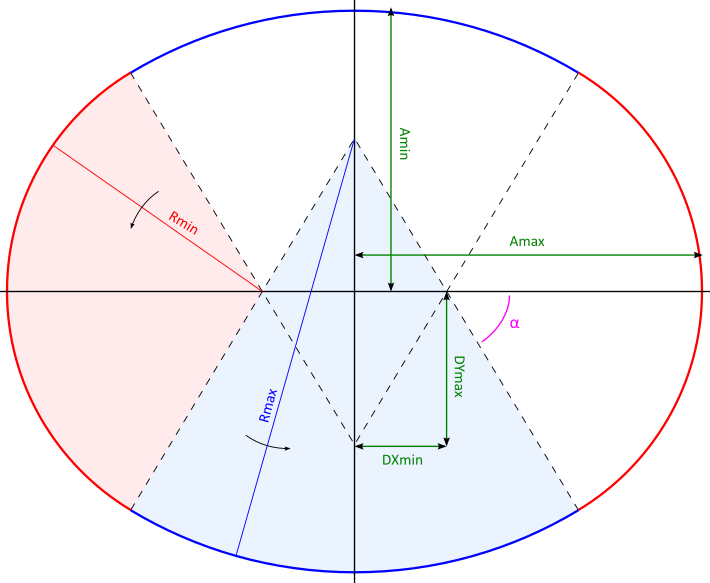

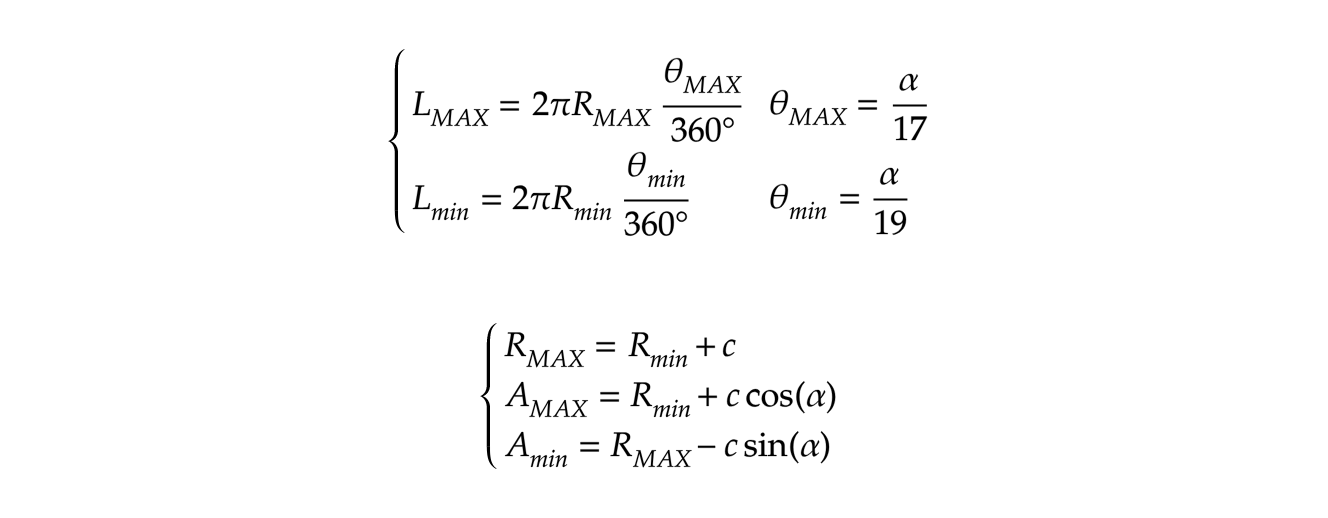

- The known data of Arena are the two axis (AMAX and Amin), the variables are the radius of the two bigger circles (RMAX), the radius of the two smaller circles (Rmin) and the angle (ALPHA) of the joining point of the arcs of circle.

- Two constraints come from geometrical relationships of the four-centers-oval, the third one is that the arches on all arcs of circles must have the same size. This constraint is fundamental for the overall graphical outcome, else we would have severe artifacts at joining points and asymmetries.

The system of equations is not trivial to solve in analytical way, but actually we don’t need a mathematically perfect solution. So after some analytical passages, we complete the solution in a numeric way (see spreasheet).

- Data

- AMAX = 76.33 m (major axis)

- Amin = 61.72 m (minor axis)

- NMAX = 17 (arches on the bigger arc of circle)

- Nmin = 19 (arches on the smaller of circle)

- Results

- ALPHA = 58.950 °

- RMAX = 95.312 m (radius of bigger arc of circle)

- Rmin = 56.102 m (radius of smaller arc of circle)

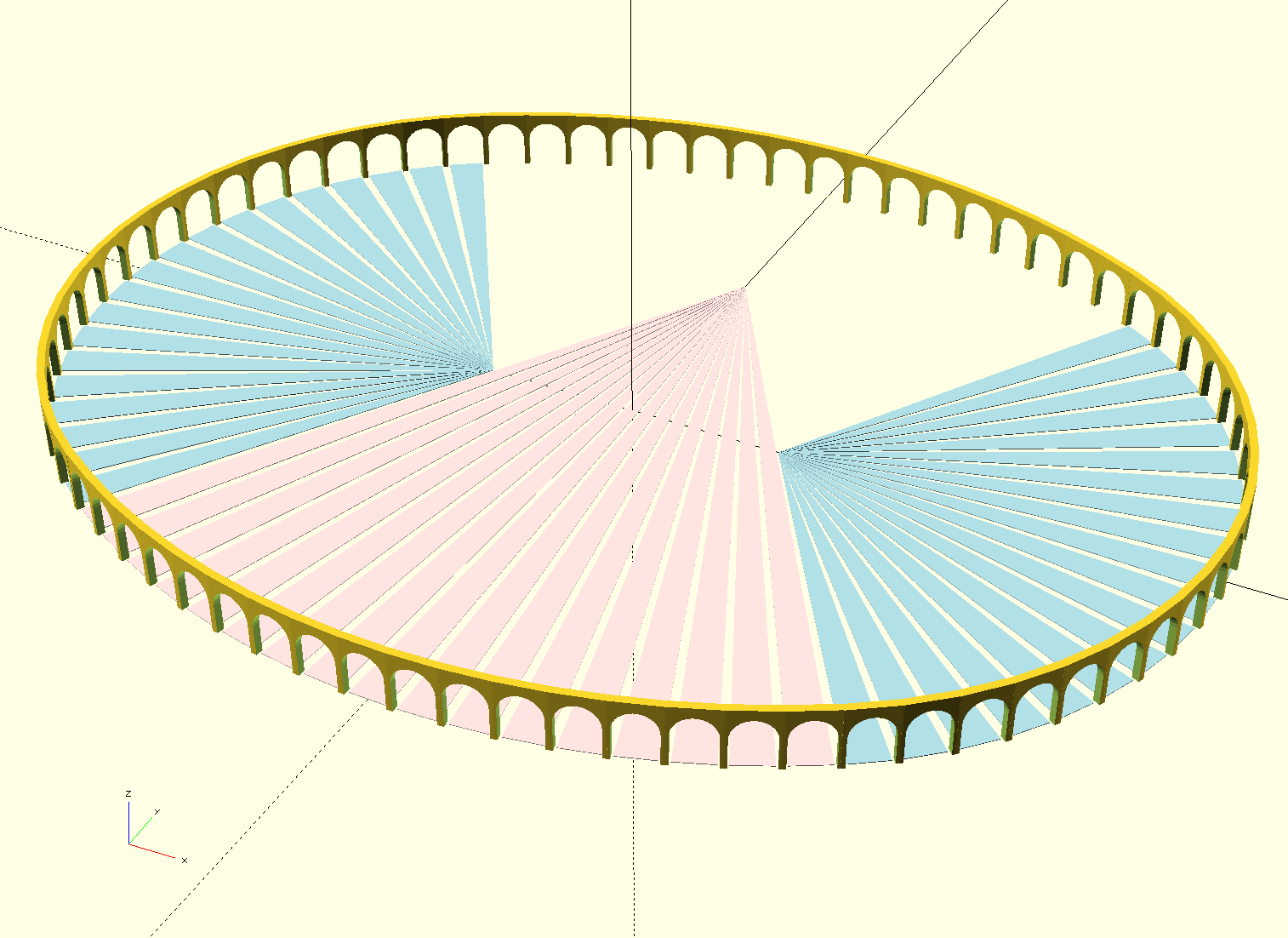

Using these parameter is now easy to create a very simple openSCAD model, using a stylized arch block placed along the arcs of circle, in order to have a quick glance. The rendering is good and show a very smooth transition at joining points.

// parameters for 4-circles oval

alfa = 58.95;

beta = 90-alfa;

rmin = 561;

rmax = 953;

dxmin = (rmax-rmin)*cos(alfa);

dymax = (rmax-rmin)*sin(alfa);

// RMAX circles

for (ii=[-8:8]) {

// 17 small arches

px = (rmax)*cos(2*beta*ii/17-90);

py = (rmax)*sin(2*beta*ii/17-90);

translate([px,py+dymax,0]) rotate([0,0,2*beta*ii/17]) arch(xx=62,yy=10,zz=80);

translate([px,-py-dymax,0]) rotate([0,0,-2*beta*ii/17]) arch(xx=62,yy=10,zz=80);

// 17 circular sectors

pxA = (rmax)*cos(2*beta*(ii-0.4)/17-90);

pyA = (rmax)*sin(2*beta*(ii-0.4)/17-90);

pxB = (rmax)*cos(2*beta*(ii+0.4)/17-90);

pyB = (rmax)*sin(2*beta*(ii+0.4)/17-90);

a = [[0,dymax],[pxA,pyA+dymax],[pxB,pyB+dymax]];

color("MistyRose") polygon(a);

}

// RMIN circles

for (ii=[-9:9]) {

// 19 small arches

c = ((ii%2)==0) ? "blue" : "gold";

px = (rmin)*cos(2*alfa*ii/19);

py = (rmin)*sin(2*alfa*ii/19);

translate([px+dxmin,py,0]) rotate([0,0,2*alfa*ii/19+90]) arch(xx=62,yy=10,zz=80);

translate([-px-dxmin,py,0]) rotate([0,0,-2*alfa*ii/19+90]) arch(xx=62,yy=10,zz=80);

// 19 circular sectors

pxA = (rmin)*cos(2*alfa*(ii-0.4)/19);

pyA = (rmin)*sin(2*alfa*(ii-0.4)/19);

pxB = (rmin)*cos(2*alfa*(ii+0.4)/19);

pyB = (rmin)*sin(2*alfa*(ii+0.4)/19);

a = [[dxmin,0],[dxmin+pxA,pyA],[dxmin+pxB,pyB]];

b = [[-dxmin,0],[-dxmin-pxA,pyA],[-dxmin-pxB,pyB]];

color("PowderBlue") polygon(a);

color("PowderBlue") polygon(b);

}

// small arch module

module arch(xx,yy,zz) {

difference() {

translate([-xx/2,-yy/2,0]) cube([xx,yy,zz]);

translate([0,0,zz/2]) rotate([90,0,0]) translate([0,0,-yy/2-5]) cylinder(d=xx-10,h=yy+10);

translate([-(xx-10)/2,-yy,-5]) cube([xx-10,2*yy,zz/2+5]);

}

}

In the next part we will focus on inner ovals and other elements of plan.